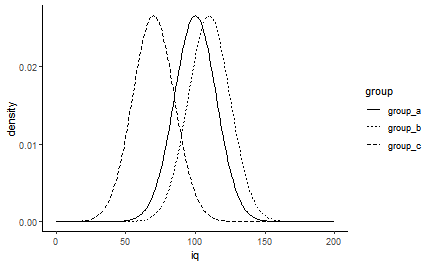

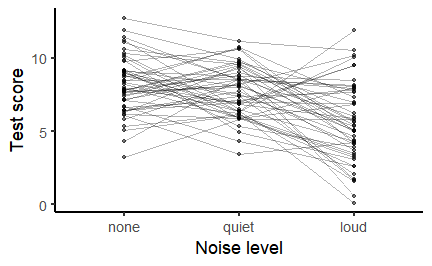

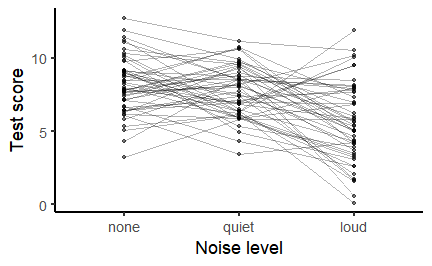

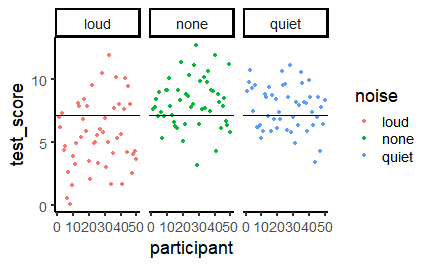

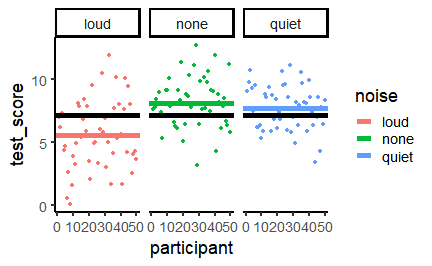

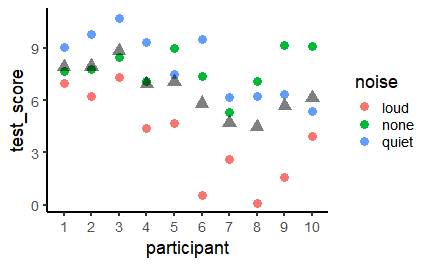

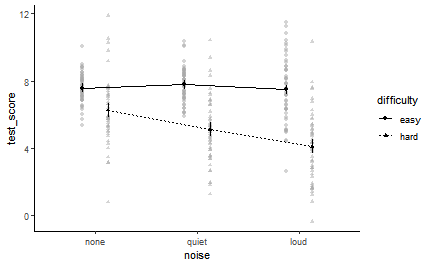

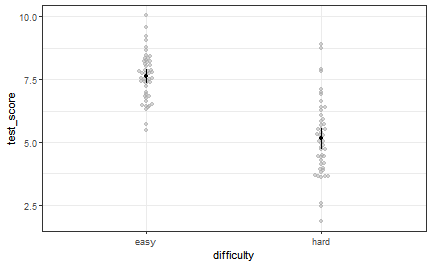

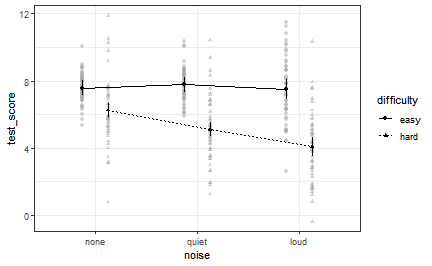

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # Repeated measures and factorial ANOVA ### 14/12/2021 --- # Multiple linear regression .pull-left[ Multiple regression is what we need with multiple predictors. ```r a <- 2 # Our intercept term b1 <- 0.65 # Our first regression coefficient X1 <- rnorm(1000, 6, 1) # Our first predictor b2 <- -0.8 # Our second regression coefficient X2 <- rnorm(1000, 3, 1) # Our second predictor err <- rnorm(1000, 0, 1) # Our error term y <- a + b1 * X1 + b2 * X2 + err # Our response variable ``` ] .pull-right[ A simple regression has one predictor... ```r lm(y ~ X1) ``` and adding predictors is easy - we use the `+` symbol! ```r lm(y ~ X1 + X2) ``` ] --- # Comparing three or more means with ANOVA The `t.test()` can only handle two groups. When we have three or more groups, we need to use a One-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). <!-- --> --- # How to run ANOVA with the `afex` package Although the standard R function for ANOVA, `aov()`, works, it can be fiddly to use. The `afex` package provides several easier methods for running ANOVA. We'll use the `aov_ez()` function. ```r noise_aov <- aov_ez(dv = "test_score", between = "noise", id = "participant", data = noise_test) ``` ``` ## Converting to factor: noise ``` ``` ## Contrasts set to contr.sum for the following variables: noise ``` --- class: inverse, middle, center # Comparing multiple means with dependent data --- # Within-subjects ANOVA When the assumption of *independence* is violated - i.e. participants contribute more than one data point, and contribute to more than one design *cell* - we need to use a *within-subjects* or *repeated-measures* ANOVA. # A worked example Our researcher from last week wanted to examine the effect of noisy environments on test performance. She recruited 150 participants and splits them into three groups who took the test with no noise, reasonably quiet noise, or loud noise. One problem here is the possibility that participants in each group just had different levels of ability. To get round this, she decides to get each participant to sit three tests, each under different levels of noise. Thus, any differences attributed to noise can't be due to test-taking ability. --- # Within-subjects ANOVA .pull-left[ ```r head(noise_test) ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 6 x 3 ## noise test_score participant ## <chr> <dbl> <int> ## 1 none 6.51 1 ## 2 none 6.82 2 ## 3 none 9.23 3 ## 4 none 6.36 4 ## 5 none 8.60 5 ## 6 none 8.21 6 ``` ] .pull-right[ .large[ Last time we simulated data with a *between-subjects* structure: One row per observation, which meant one row per participant. ] ] --- # Within-subjects ANOVA .pull-left[ .large[ This time, it's the same participants in each condition. There's still one row per observation, but now there are three rows per participant - one for each observation in each of the three conditions. ] ] .pull-right[ ```r arrange(noise_test_within, participant) ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 150 x 3 ## noise test_score participant ## <chr> <dbl> <int> ## 1 none 7.68 1 ## 2 quiet 9.06 1 ## 3 loud 7.01 1 ## 4 none 7.78 2 ## 5 quiet 9.82 2 ## 6 loud 6.26 2 ## 7 none 8.46 3 ## 8 quiet 10.7 3 ## 9 loud 7.31 3 ## 10 none 7.12 4 ## # ... with 140 more rows ``` ] --- # Plotting the data .pull-left[ <!-- --> ] .pull-right[ .large[ It looks like loud noise has a really detrimental effect on performance; it also looks like loud noise makes performance more *variable*. ```r noise_test_within %>% group_by(noise) %>% summarise(variance = var(test_score)) ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 3 x 2 ## noise variance ## <chr> <dbl> ## 1 loud 7.39 ## 2 none 3.81 ## 3 quiet 3.12 ``` ] ] --- # Plotting the data .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ Furthermore, scores tend to be positively correlated (albeit weakly) across tests - people who score well in one situation tend to score well in other situations. ```r noise_test_within %>% pivot_wider(names_from = "noise", values_from = "test_score") %>% select(2:4) %>% cor() %>% round(2) ``` ``` ## none quiet loud ## none 1.00 0.30 0.32 ## quiet 0.30 1.00 0.19 ## loud 0.32 0.19 1.00 ``` ] --- # The mean as a model (again) .pull-left[ <!-- --> ] .pull-right[ .large[ The grand mean test score is 6.45, shown by the black line. The total variability in our data is the sum of the squared differences from the grand mean - the Total Sum of Squares, `\(SS_t\)`. ] ] --- # The group means as a model .pull-left[ <!-- --> ] .pull-right[ .large[ Our Model Sum of Squares - `\(SS_m\)` - is the sum of the squared differences of each group's mean from the *grand mean*. The group means are shown here using coloured lines. This is just the same as it is for a between-subjects ANOVA. But the next step is different! ] ] --- # Within-subject variability .pull-left[ <!-- --> ] .pull-right[ .large[Here, we need the within-participant sum of squares - `\(SS_w\)`. This is the sum of squared differences of each participant's scores from their individual mean. Each participant's mean is marked using a triangle, while scores from individual conditions are marked with points.] ] --- # The leftovers, the mean squares, and the F-ratio Finally, we can calculate the Residual sum of squares - `\(SS_r\)` by subtracting the model sum of squares - `\(SS_m\)` - from the within-subjects sum of squares - `\(SS_w\)`. We then calculate the Model Mean Square Error - `\(MS_m\)` - and Residual Mean Square Error - `\(MS_r\)` - the same way as last time, using the degrees of freedom - `$$MS_m = \frac{SS_m}{df_m}$$` `$$MS_r = \frac{SS_r}{df_r}$$` And we calculate the *F-ratio* in the same way as last time. `$$F = \frac{MS_m}{MS_r}$$` --- # Between- versus within-subject ANOVA .large[ 1. The underlying computations are mostly the same, but differ in how they treat the variability 2. Within-subject designs use within-subject variability - Within-subject variability is often much lower than between-subject variability - People function as their own controls! 3. Since the variance within-subjects is generally lower than between-subjects, within-subject designs typically have more *statistical power* i.e. are more *sensitive*. 4. However, there is a risk of *order* or *practice* effects with within-subject designs. ] --- class: inverse, center, middle # How to run a one-way within-subjects ANOVA --- # Within-subjects ANOVA with `afex` Just like last week, we can use `aov_ez()` from the `afex` package. Instead of passing a parameter called *between*, we pass one called *within*. ```r noise_within_aov <- aov_ez(dv = "test_score", id = "participant", within = "noise", data = noise_test_within) noise_within_aov ``` ``` ## Anova Table (Type 3 tests) ## ## Response: test_score ## Effect df MSE F ges p.value *## 1 noise 1.81, 88.54 3.93 26.54 *** .212 <.001 ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '+' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Sphericity correction method: GG ``` --- # The sphericity assumption *Sphericity* is the equivalent to the homogeneity of variance assumption when there are three or more levels of a repeated measures factor. `afex` applies Greenhouse-Geisser correction *by default* - it adapts the *degrees of freedom* to compensate for different variances. ```r noise_within_aov ``` ``` ## Anova Table (Type 3 tests) ## ## Response: test_score ## Effect df MSE F ges p.value *## 1 noise 1.81, 88.54 3.93 26.54 *** .212 <.001 ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '+' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## *## Sphericity correction method: GG ``` --- # Effect size *ges* in the output stands for **Generalized eta-squared** - `\(\eta_g^2\)` This tells us the proportion of variance explained, *similar* to `\(r^2\)`. ```r noise_within_aov ``` ``` ## Anova Table (Type 3 tests) ## ## Response: test_score ## Effect df MSE F ges p.value *## 1 noise 1.81, 88.54 3.93 26.54 *** .212 <.001 ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '+' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Sphericity correction method: GG ``` --- # Within-subjects ANOVA .large[ We can follow up the significant effect in the same way as last time: ```r pairs(emmeans(noise_within_aov, ~noise)) ``` ``` ## contrast estimate SE df t.ratio p.value ## none - quiet 0.413 0.311 49 1.328 0.3867 ## none - loud 2.558 0.394 49 6.491 <.0001 ## quiet - loud 2.145 0.417 49 5.141 <.0001 ## ## P value adjustment: tukey method for comparing a family of 3 estimates ``` Performance in the **quiet** and **no noise** conditions is significantly better than performance in the **Loud noise** condition, but they aren't significantly different from each other. ] --- # Reporting the results ```r noise_within_aov ``` ``` ## Anova Table (Type 3 tests) ## ## Response: test_score ## Effect df MSE F ges p.value ## 1 noise 1.81, 88.54 3.93 26.54 *** .212 <.001 ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '+' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Sphericity correction method: GG ``` .large[ "There was a significant effect of noise level on test scores, [F(1.81, 88.54) = 26.54, *p* < .001]. Test performance without noise and with quiet noise did not significantly differ (*p* = .5), but both were significantly better than performance in the loud noise condition (*p*s < .001)." ] --- class: inverse, middle, center # Comparing multiple means with multiple categorical predictors --- # Factorial ANOVA .pull-left[ .large[ Our researcher now wonders whether the level of noise matters more for tests that are hard compared to tests that are relatively easy. So she runs the study again, with the same three noise conditions, but now splits the participants into two more conditions. Half of the participants take an easy test; the other half take a hard test. ] ] .pull-right[ ```r noise_test_mixed ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 300 x 4 ## noise difficulty test_score participant ## <chr> <chr> <dbl> <int> ## 1 none hard 11.9 1 ## 2 none hard 6.26 2 ## 3 none hard 0.774 3 ## 4 none hard 7.69 4 ## 5 none hard 6.27 5 ## 6 none hard 3.13 6 ## 7 none hard 4.82 7 ## 8 none hard 6.60 8 ## 9 none hard 6.93 9 ## 10 none hard 4.71 10 ## # ... with 290 more rows ``` ] --- # What design does the researcher have? .large[ Factorial designs can be purely within-subjects, purely between-subjects, or a mixture of the two. There can be any number of factors with any number of levels. The resulting experiment has **two** independent, categorical variables, and thus two *factors*. The factor "test difficulty" has two levels - "easy" and "hard". It is a *between-subjects* factor. The factor "noise" has three levels - "none", "quiet", and "loud". It is a *within-subjects* factor. This calls for a Two-Way, `\(2 \times 3\)` Mixed ANOVA. ] --- # The structure of the data .pull-left[ Since each participant takes part in all three noise conditions, there are three rows per participant. ```r noise_test_mixed %>% arrange(participant) ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 300 x 4 ## noise difficulty test_score participant ## <chr> <chr> <dbl> <int> ## 1 none hard 11.9 1 ## 2 quiet hard 7.27 1 ## 3 loud hard 7.53 1 ## 4 none hard 6.26 2 ## 5 quiet hard 4.44 2 ## 6 loud hard 5.16 2 ## 7 none hard 0.774 3 ## 8 quiet hard 3.55 3 ## 9 loud hard 1.23 3 ## 10 none hard 7.69 4 ## # ... with 290 more rows ``` ] .pull-right[ But since difficulty is between-subjects, the participant ID numbers differ across easy and hard difficulties. ```r noise_test_mixed %>% group_by(difficulty) %>% slice(1:3) ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 6 x 4 ## # Groups: difficulty [2] ## noise difficulty test_score participant ## <chr> <chr> <dbl> <int> ## 1 none easy 8.98 51 ## 2 none easy 6.81 52 ## 3 none easy 6.84 53 ## 4 none hard 11.9 1 ## 5 none hard 6.26 2 ## 6 none hard 0.774 3 ``` ] --- # Mixed factorial ANOVA with `afex` .large[ We enter *between* factors using the **between** argument; *within* factors using the **within** argument. ] ```r noise_aov_mixed <- aov_ez(id = "participant", dv = "test_score", between = "difficulty", within = "noise", data = noise_test_mixed) ``` ``` ## Converting to factor: difficulty ``` ``` ## Contrasts set to contr.sum for the following variables: difficulty ``` --- # Mixed factorial ANOVA with `afex` ```r noise_aov_mixed ``` ``` ## Anova Table (Type 3 tests) ## ## Response: test_score ## Effect df MSE F ges p.value *## 1 difficulty 1, 98 4.65 98.53 *** .344 <.001 *## 2 noise 1.98, 194.13 2.15 15.08 *** .069 <.001 *## 3 difficulty:noise 1.98, 194.13 2.15 13.09 *** .060 <.001 ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '+' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Sphericity correction method: GG ``` .large[ Looks like **everything** is significant! ] --- # A worked example .pull-left[ Here's a similar plot to the one I produced earlier, but using `afex_plot()` instead of `ggplot()`. ```r afex_plot(noise_aov_mixed, x = "noise", trace = "difficulty", error = "between") + theme_classic() ``` ``` ## Warning: Panel(s) show a mixed within-between-design. ## Error bars do not allow comparisons across all means. ## Suppress error bars with: error = "none" ``` It seems pretty obvious from this plot that there's an effect of noise when the test is hard, but not so much when the test is easy. This is an **interaction** effect. ] .pull-right[  ] --- # Post-hoc tests We need to follow up a significant interaction to work out, statistically, what is driving the interaction. One way to do this is with post-hoc tests. With post-hoc tests, we compare every possible pair of means to each other using t-tests. First let's get all the means using `emmeans()`. ```r all_means <- emmeans(noise_aov_mixed, ~noise * difficulty) all_means ``` ``` ## noise difficulty emmean SE df lower.CL upper.CL ## none easy 7.58 0.216 98 7.15 8.01 ## quiet easy 7.78 0.221 98 7.34 8.22 ## loud easy 7.49 0.288 98 6.92 8.06 ## none hard 6.25 0.216 98 5.82 6.68 ## quiet hard 5.11 0.221 98 4.67 5.55 ## loud hard 4.08 0.288 98 3.51 4.65 ## ## Confidence level used: 0.95 ``` --- # Post-hoc tests Then we use the `pairs()` function to test them all against each other. ```r pairs(all_means) ``` ``` ## contrast estimate SE df t.ratio p.value ## none easy - quiet easy -0.2022 0.278 98 -0.728 0.9781 ## none easy - loud easy 0.0866 0.296 98 0.292 0.9997 ## none easy - none hard 1.3285 0.306 98 4.346 0.0005 ## none easy - quiet hard 2.4708 0.309 98 7.988 <.0001 ## none easy - loud hard 3.5003 0.360 98 9.731 <.0001 ## quiet easy - loud easy 0.2888 0.302 98 0.958 0.9300 ## quiet easy - none hard 1.5307 0.309 98 4.948 <.0001 ## quiet easy - quiet hard 2.6730 0.313 98 8.541 <.0001 ## quiet easy - loud hard 3.7025 0.363 98 10.204 <.0001 ## loud easy - none hard 1.2418 0.360 98 3.452 0.0104 ## loud easy - quiet hard 2.3842 0.363 98 6.571 <.0001 ## loud easy - loud hard 3.4136 0.407 98 8.395 <.0001 ## none hard - quiet hard 1.1424 0.278 98 4.112 0.0011 ## none hard - loud hard 2.1718 0.296 98 7.325 <.0001 ## quiet hard - loud hard 1.0295 0.302 98 3.413 0.0117 ## ## P value adjustment: tukey method for comparing a family of 6 estimates ``` --- # Post-hoc tests .large[ 1. Should only be used following a *significant* interaction. 2. Leads to a lot of comparisons - N(N-1) / 2, where N is the number of means. So it's **extremely important** to correct for multiple comparisons! - Numerous methods exist; fortunately, `emmeans()` and `pairs()` handle this for us using Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference (HSD). 3. Can be difficult to interpret, especially with more than two factors. If in doubt, *look at the plots*. ] --- # Simple effects An alternative way is with *simple effects*. We can effectively run separate analyses at different levels of one of the factors. Here I look at the means for each level of noise separately for the two levels of difficulty. ```r emmeans(noise_aov_mixed, "noise", by = "difficulty") ``` ``` ## difficulty = easy: ## noise emmean SE df lower.CL upper.CL ## none 7.58 0.216 98 7.15 8.01 ## quiet 7.78 0.221 98 7.34 8.22 ## loud 7.49 0.288 98 6.92 8.06 ## ## difficulty = hard: ## noise emmean SE df lower.CL upper.CL ## none 6.25 0.216 98 5.82 6.68 ## quiet 5.11 0.221 98 4.67 5.55 ## loud 4.08 0.288 98 3.51 4.65 ## ## Confidence level used: 0.95 ``` --- # Simple effects Now we run post-hoc tests separately within each level of difficulty. ```r pairs(emmeans(noise_aov_mixed, "noise", by = "difficulty")) ``` ``` ## difficulty = easy: ## contrast estimate SE df t.ratio p.value ## none - quiet -0.2022 0.278 98 -0.728 0.7477 ## none - loud 0.0866 0.296 98 0.292 0.9540 ## quiet - loud 0.2888 0.302 98 0.958 0.6054 ## ## difficulty = hard: ## contrast estimate SE df t.ratio p.value ## none - quiet 1.1424 0.278 98 4.112 0.0002 ## none - loud 2.1718 0.296 98 7.325 <.0001 ## quiet - loud 1.0295 0.302 98 3.413 0.0027 ## ## P value adjustment: tukey method for comparing a family of 3 estimates ``` --- # Simple effects .large[ 1. Often easier to interpret (especially when there are more than two factors). 2. Fewer comparisons so less stringent correction for multiple comparison, and higher power to detect differences. 3. Not always obvious which factor to separate on. Sometimes it's easier to interpret one way than the other! Again, *use plots as a guide*. ] --- # What about the main effects? I skipped straight to the interaction earlier. Why? ```r noise_aov_mixed ``` ``` ## Anova Table (Type 3 tests) ## ## Response: test_score ## Effect df MSE F ges p.value *## 1 difficulty 1, 98 4.65 98.53 *** .344 <.001 *## 2 noise 1.98, 194.13 2.15 15.08 *** .069 <.001 ## 3 difficulty:noise 1.98, 194.13 2.15 13.09 *** .060 <.001 ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '+' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Sphericity correction method: GG ``` There are significant main effects of *noise* and *difficulty*. --- # The main effect of noise There's a significant main effect of noise. Let's look at the plot. ```r afex_plot(noise_aov_mixed, ~noise, error = "within") + theme_classic() ``` <!-- --> --- # The main effect of noise As noise increases, test performance goes down. ```r emmeans(noise_aov_mixed, ~noise) ``` ``` ## noise emmean SE df lower.CL upper.CL ## none 6.91 0.153 98 6.61 7.22 ## quiet 6.44 0.156 98 6.13 6.76 ## loud 5.79 0.203 98 5.38 6.19 ## ## Results are averaged over the levels of: difficulty ## Confidence level used: 0.95 ``` --- # The main effect of difficulty Let's look at the plot for difficulty. ```r afex_plot(noise_aov_mixed, ~difficulty, error = "between") + theme_bw() ``` <!-- --> --- # The main effect of difficulty Test performance is much higher when the test is easy than when it's hard. ```r emmeans(noise_aov_mixed, ~difficulty) ``` ``` ## difficulty emmean SE df lower.CL upper.CL ## easy 7.62 0.176 98 7.27 7.97 ## hard 5.15 0.176 98 4.80 5.50 ## ## Results are averaged over the levels of: noise ## Confidence level used: 0.95 ``` --- # Are these effects meaningful? .pull-left[ ```r afex_plot(noise_aov_mixed, ~noise, trace = "difficulty") + theme_bw() ``` ``` ## Warning: Panel(s) show a mixed within-between-design. ## Error bars do not allow comparisons across all means. ## Suppress error bars with: error = "none" ``` There is clearly no significant effect of noise when the test is easy, so the main effect of noise is uninterpretable. But there is *always* an effect of test difficulty, so the main effect of test difficulty *is* interpretable. **Main effects are not always interpretable in the presence of an interaction!** ] .pull-right[  ] --- class: inverse, middle, center # Reporting factorial ANOVA results --- # Reporting factorial ANOVAs .large[ Make sure that somewhere in your text is a description of which type of ANOVA you are running, and exactly what factors are involved. A couple of examples: 1. We conducted a two-way repeated measures ANOVA with the factors Noise (None, Quiet, or Loud) and Difficulty (Easy or Hard). 2. We conducted a `\(2 \times 3\)` mixed ANOVA. The between-subjects factor was Difficulty (Easy or Hard), while Noise was a repeated-measures factor (None, Quiet, or Loud) ] --- # Reporting factorial ANOVAs ``` ## Anova Table (Type 3 tests) ## ## Response: test_score ## Effect df MSE F ges p.value *## 1 difficulty 1, 98 4.65 98.53 *** .344 <.001 ## 2 noise 1.98, 194.13 2.15 15.08 *** .069 <.001 ## 3 difficulty:noise 1.98, 194.13 2.15 13.09 *** .060 <.001 ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '+' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Sphericity correction method: GG ``` There was a significant main effect of Difficulty [F(1, 98) = 98.54, p < .001], with better test performance when the test was easy (mean = 7.62) compared to when the test was hard (mean = 5.15). *NB: since there are only two levels, no post-hoc test is necessary!* --- # Reporting factorial ANOVAs ``` ## Anova Table (Type 3 tests) ## ## Response: test_score ## Effect df MSE F ges p.value ## 1 difficulty 1, 98 4.65 98.53 *** .344 <.001 *## 2 noise 1.98, 194.13 2.15 15.08 *** .069 <.001 ## 3 difficulty:noise 1.98, 194.13 2.15 13.09 *** .060 <.001 ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '+' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Sphericity correction method: GG ``` There was a significant main effect of noise [F(1.98, 194.13) = 15.08, *p* < .001]. Test scores were significantly lower with loud noise (5.79) than with no noise (mean = 6.91; *p* < .001) or with quiet noise (6.44; *p* = .005). There was no significant difference between the "no noise" and "quiet noise" conditions (*p* =.06). --- # Reporting factorial ANOVAs ``` ## Anova Table (Type 3 tests) ## ## Response: test_score ## Effect df MSE F ges p.value ## 1 difficulty 1, 98 4.65 98.53 *** .344 <.001 ## 2 noise 1.98, 194.13 2.15 15.08 *** .069 <.001 *## 3 difficulty:noise 1.98, 194.13 2.15 13.09 *** .060 <.001 ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '+' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Sphericity correction method: GG ``` Finally, there was also a significant interaction between Noise and Difficulty [F(1.98, 194.13) = 13.09, p < .001], see Figure X. Simple main effects analysis, corrected for multiple comparisons using Tukey's HSD, found that when test difficulty was Easy, there were no significant differences between any level of Noise (all *p*s > .58). However, in the Hard condition, test performance was significantly better when there was no noise (mean = 6.25) compared to when there was either quiet (5.11; *p* < .001) or loud noise (4.08, *p* < .001). Performance was also significantly worse for loud noise relative to quiet noise (*p* = .002).